by PhD candidate Rebecca Repper

Photography is a popular medium for understanding, representing and communicating our collective past and cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible. I am particularly fascinated with photography for this very reason. It permeates through all types of collections and institutions - Galleries, Museums, Libraries and Archives, of Art, Science, History, Technology and more - but how it is represented in those collections has very real impacts on how we as researchers and as the public of those collecting bodies can access and understand the photographs and photography.

PhD candidate Rebecca Repper

Western Australia is represented in and by millions of photographs within public collecting institutions, not least the partner institutions of the Collecting the West project. Reaching an understanding of what 'WA' has collected, and what is of 'WA' that has been collected elsewhere, is fragmented through the very different and discrete systems that must be consulted that exist in each of these organisations. This problem is compounded by the fact that institutional collection management systems, the catalogues you and I consult when searching, are often ill suited to record the complex information related to photographic items.

In seeking to understand these issues, I will research the policies and decisions that have led to how WA's photographic record is documented, and in what way these impact our understanding and access to the photographic material of Western Australia. Moreover, I seek to explore through an applied investigation if these complex and disparate collections can effectively collate into a single interface using the International Standard CIDOC CRM, a process known as interoperability. Through this applied investigation I will determine whether the resulting dataset can be effectively queried and therefore whether this is a methodology through which we can access and research WA's collections collectively. I hope to establish whether there are any mitigating factors inherent within the institutional datasets, the CIDOC CRM, or the photographic medium itself that hinder the practical implementation of the international standard.

My research is in its very early months. I have been concentrating so far on some fantastic literature from the past 30 years that has focused on the complex and problematic place of photographs and photography within collecting institutions. I recommend Gaby Porter's seminal 1989 paper on this topic, 'The Economy of Truth: Photography in Museums', which is still very much applicable today,[1] as well as Elizabeth Edwards online blog series Institutions and the Production of 'Photographshosted by FotomuseumWinterthur. My applied research will require technical skills associated with collection management standards and digital data conversion, so I am embarking on a month of training in the UK in July. I will be attending the Digital Humanities Oxford Summer School and the ResearchSpace symposium 'Building Cultural Heritage Knowledge', as well as undertaking a fortnight's placement with the ResearchSpace team at The British Museum to develop my understanding of CIDOC CRM and to test my first photography dataset (from the State Library of WA) with this standard. I look forward to reporting back and letting you know how my research develops.

[1] Porter, G., 1989. The Economy of Truth: Photography in Museums. Ten.8, 34, pp.20–33.

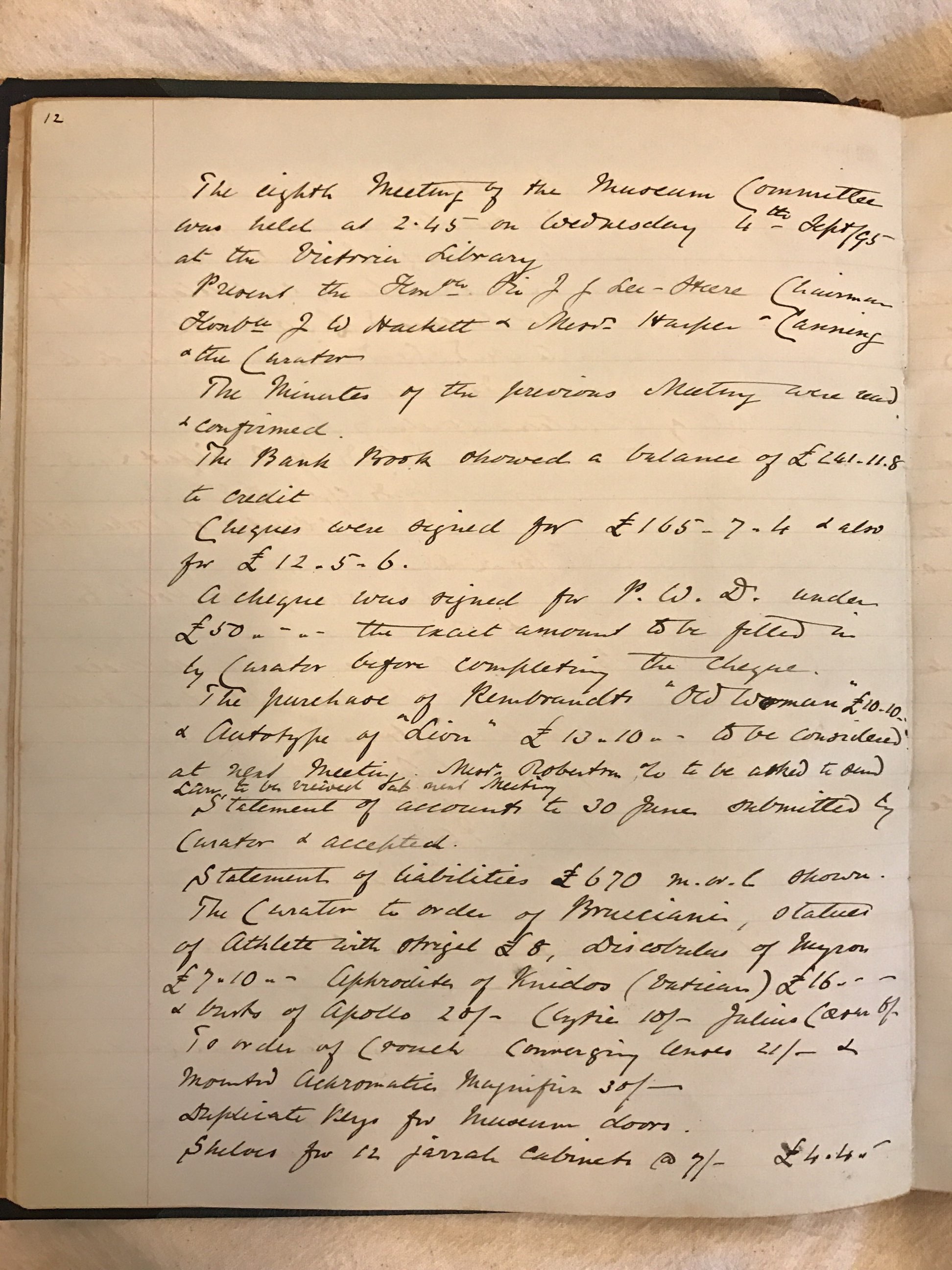

Banner image: Glass Plate Negatives in carry case (UCL Institute of Archaeology Collections), photograph by Rebecca Repper.